Take a moment to imagine a world without colonization. Somewhere along what is now called North America, a woman is purposefully grinding corn while her children gather berries. On the Pacific coast, fish are being pulled from nets that were lovingly woven together.

In the Andes, potatoes are put into underground pits in preparation for winter long before the frost sets in.

These are not romantic images, but rather the product of generations straining to achieve survival. Rather than stumbling upon a solution, Indigenous people studied nature in-depth, observing their surroundings to learn how to live in harmony with the environment, and passed this knowledge down to future generations. Nature’s spiritual respect guided them alongside profound comprehension of land and body.

Native diets before disruption were simple yet whole, with no wrappings or preservatives, such as boxes, cans, or labels.

Every meal begins with a prayer, followed by gratitude and remembrance. Not appreciation for creation, but instead life. All living beings honor their sustenance – whether it’s water from rivers, a bountiful harvest, or nourishment from forests and gardens. Food is a blend of sacred traditions accompanying birth, marriage, grief, and culture.

Key Takeaways

- Colonialism shattered native food systems, ultimately disrupting their dietary patterns.

- The resultant diet dictated the overall health and cultural heritage of the indigenous people.

- Food became an instrument of control through rations, boarding schools, and land dispossession.

- Sovereignty over native foods today acts as a means of self-defense as well as collective therapy.

- Restoration of ancestral diets do more than restore one’s memory; it brings honor and a sacred bond with the land.

When The Ship Arrived, The Hunger Began

Here comes the ship, expanding borders into new territories with ‘under new management’ signs written in bold letters. Ships brought a new sense of territorial conquest, replacing the fisherman’s sense of freedom to cast and the wanderer’s ability to roam into a new norm. Every ‘displaced’ citizen had a gaping hole of land where their home previously existed. Their homes were no longer shelters but sought after properties which paved the way towards a new state of hunger coming both physically and psychologically.

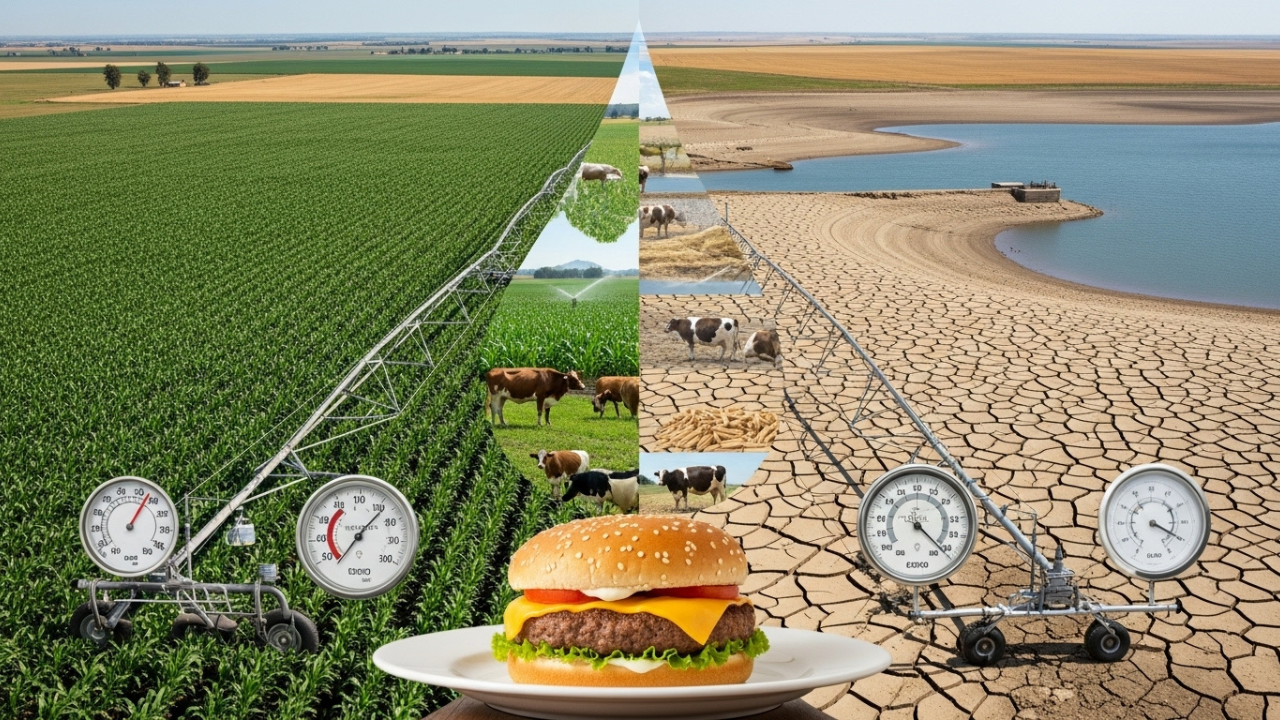

The Colonizers did not attempt to integrate with the indigenous methods of food production. Instead, they brought their own systems and declared them civilized and better. Wheat was grown on land where corn, maize crops or other crops had existed and flourished for thousands of years.

Livestock farms replaced areas where buffalo once roamed in herds so thick they shook the ground beneath them. Buffalo Herd Monoculture replaced traditional farms. The Pre-Columbian Cultures Diverse diet of tribal peoples was systematically eliminated to give way to agriculture imposed and controlled by Europeans logic reductionism not local wisdom.

The imposition of these changes does not tell us that this was a gentle transition. It was forced change. In some of these places, native techniques and customs of farming were outlawed, prohibited, and stripped bare. Banning the Spiritual food practices or semi-religious acts of harvesting has been ridiculed and criminalized. Even the seed—carried for centuries in bundles, within medicine bags, or stored in clay jars—were taken, replaced or forgotten under pressure. The Broken System: the remnants of what was available became, not just an empty shell, but a community asked to survive without its roots, gradually dismantled.

From Sacred Foods To Commodity Rations

Imagine being told that your favourite food from childhood is now banned globally. To make matters worse, the only thing you can subsist on is a can of lard and a tin of flour. This scenario closely resembles the diet handed to natives on missions, reservations and during relocation around the world. The replacement food options did not guarantee nutrition or well-being. Rather, they were devoid of meaningful content; unfamiliar to prepare and stripped of elements that constituents nourish. These replacements were merely lightweight packs meant for survival.

Essentially, everything indigenous communities consumed turned into processed rations. Sustainably sourced ingredients underwent unrecognizable alterations, stripped of any nutritional value, leaving one dependant on the colonial vending machine. Nutritionally poor food became commonplace in indigenous cultures. From repackaged powdered cheese and milk, to white sugar, and flour. Colonial rule understood food was a tool to secure control. Whoever accepted the new regulations received a barbaric sustenance system, while anyone who resistant was forced to starve.

The punishment was not limited to just rations. The “kill the Indian, save the man” boarding schools exposed children to the Western way of life, including their food, which had to be consumed in silence and with a sense of guilt. The use of Native ingredients was strictly prohibited as was the use of Native languages during meals lest one wants to be punished. Students were conditioned to believe that the food served by their families was filthy, primitive, or uncivilized. What was inflicted on those students in those dining halls was not simply a change in diet. It was a plate of identity obliteration.

The Health Crisis Born From Colonized Diets

It did not take long for the consequences to surface. After just a few generations, once vibrant, active, and robust communities started experiencing ailments that had been alien to them. Heart disease, obesity, and diabetes became rampant. There was a drastic shift from subsistence agriculture which relied on fishing and gardening to processed foods laden with sugar and devoid of quality. What was once cherished as bountiful turned into a plastic-wrapped and canned nightmare.

However, it is not just about an illness. The severing of ties to traditional cuisine has psychological significance. When you are unable to make the dish your grandmother used to, when the plants you used to collect and make are now gated off or cemented over, this feeling transcends appetite—it is sorrow. Such sorrow becomes constant. It influences the way the youth develop. It influences the way the old ones are remembered. It influences how restoration has to start.

A person’s wellbeing is not solely determined by their diet. It is also a question of what ‘you’ have lost.

Memory Isn’t Gone, It’s Just Buried

But here’s something important. The memory of native food ways didn’t vanish. Instead, it was obscured, deeply hidden, but never obliterated. Elders safeguarded seeds in ancient vessels. Recipes were handed down at dusk, whispered in soft voices. Harvest songs were hummed in gardens unseen by anyone. And now, that incomprehensible memory is rising to the surface once again.

Indigenous peoples across the Americas and other places are taking back control of their food systems. They’re tilling the soil of their ancestral lands. Hunting and fishing are no longer being done solely for recreation, but rather as a means of forging deeper bonds. Children are being taught how to properly sow, gather, and cook— not from pre-packaged containers, but straight from their fields.

In the Southwest, some pueblos are coming back to the growing of traditional blue corn. In the Northern regions, First Nations are started reviving wild rice gathering. In Alaska, salmon fishing is being reintroduced as a rite of passage, not solely for economic reasons. This isn’t looking back wistfully. It’s about healing. When you restore traditional foods, you restore language, ceremony, and pride.

Reclaiming Sovereignty, One Meal At A Time

Every nation has a pending right to self-determination – to weave their own food system – and indigenous peoples all over the world strive for that food sovereignty. As deeply interconnected to colonialism’s legacy as it may be, healing the waters of memory is not only agricultural, it is political, and it is spiritual.

Elder-youth mentorship programs are being created. Community gardens are sprucing up. Cuisines from mobile kitchens teach traditional cooking. Indigenous chefs are inspiring movements that infuse contemporary culinary techniques with ancestral ingredients. With every effort made, the goal is clear: reintegrating with food is equally as important as self-identification, if not more.

The chains of colonization may supersede all boundaries, but that does not stop the suppressed hunger for one’s roots.

Looking At Today’s Plate With Open Eyes

Now allow me to wonder with you for a moment, dear reader. When you look at a portion of food, do you know its source? Do you know what land gave birth to it? Do you know the hands that harvested it, and which tales were suppressed for it to grow? Comprehending the ways in which colonialism transformed indigenous diets is not only for the purpose of history. It is for anyone who quites literally consumes food. As it stands, the present food systems are still reliant upon control, access, and ownership which are remnants of yesteryear.

Indigenous peoples continue to be more vulnerable to food insecurity. They continue to reside in regions with inadequate availability of fresh food ingredients. They continue to pursue the opportunity to hunt, fish, forage, and cultivate. Moreover, most policies budgeted regarding food aid, land concessions, and agriculture spending are carved out of an framework devoid of indigenous consultation.

Thus the question is: what should be done from this point onward? And the answer is: we make different kinds of representation. We make active policies for native people and programs. We act on policies that allow indigenous peoples to reclaim land and give land back. We knit fences around silenced narrative fragments that circulate in anthropological discourses.

My Opinion

Let us go back to the main point; the woman whom we started with, sitting alongside the river as she grinds corn. She works meticulously to achieve her aims, using her machine as an instrument. She encapsulates unexpressed or secret knowledge—no instructions are necessary. She has heard it sung, witnessed its preparation, and absorbed it, being taught to feel.

When claiming that colonialism altered native component parts of a meal, there is a vivid portrait in the complexities of human and nature’s interrelations infused with time, space, the sacred, and the unseen.

To comprehend a particular point of history, analyze what food recursos became forbidden, and to support healing efforts paying attention to what is being cultivated serves the best healing.

This act goes beyond physical nutrition. It depicts the restoration of existence beyond the perceived reality; a reality previously thought gone, yet patiently waiting to be restored for it served. Stitched together with every regained food source, every revered harvest, and every collective celebration.

Leave a Reply